(longread)

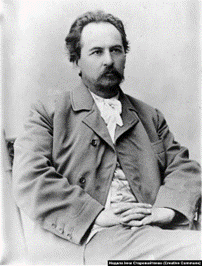

Yevhen Chykalenko lived in a time when loving Ukraine was not only difficult but dangerous. Born in 1861 into a wealthy family, he could have chosen a safe and comfortable life as a landowner in the Russian Empire. But instead, he chose to struggle — not with weapons, but through words, books, and, most importantly, financial support for those who were building Ukrainian culture.

“It’s easy to love Ukraine to the depth of your soul. Try to love it to the depth of your pocket!” – this phrase by Chykalenko best reflects his life path. He didn’t just admire the idea of the Ukrainian revival — he invested all his fortune into it.

First Steps: Odesa – A City of Awakening

Chykalenko began his civic activities in the 1890s. In 1894, he moved to Odesa, one of the centers of intellectual life. There, he joined the Odesa Ukrainian Hromada — a circle of lecturers, lawyers, and teachers dedicated to preserving the Ukrainian language and culture. They collected and systematized Ukrainian words, which led to a dictionary published in Lviv between 1893 and 1898.

In Odesa, Chykalenko met many influential Ukrainian figures. He supported them not only with words but also financially, making many projects possible.

He helped found the “Charitable Society,” which published affordable books in Ukrainian. During this time, he built ties with Ukrainians in Halychyna and began a long collaboration with Mykhailo Hrushevsky.

Chykalenko also subscribed to scholarly and literary journals to support the Ukrainian word. His efforts covered both educational and organizational work.

Kyiv: The Center of the Ukrainian Cause

In 1900, Chykalenko moved to Kyiv, which he considered the heart of the Ukrainian movement. There, he joined the Old Kyiv Hromada—the “flower of the Ukrainian intelligentsia.” Together with Hromada, he worked on compiling a Ukrainian dictionary.

He arranged for Borys Grinchenko to lead the lexicographic work and funded this ambitious project.

He also joined the editorial team of the journal Kievskaya Starina, heading the fiction department and personally investing in its publication. He organized contests, awards, and supported young authors.

His home in Kyiv became a meeting place for writers, scholars, and politicians. Vynnychenko, Kotsiubynsky, Saksahansky and many other authors visited Chykalenko. They discussed new works, political ideas, and Ukraine’s future.

A Patron of Ukrainian Journalism

Starting in 1905, the newspaper Hromadska Dumka appeared, later renamed Rada. It was the first daily Ukrainian-language newspaper in the Dnipro region. Chykalenko was its visionary and main financial backer.

The newspaper became a vital platform for Ukrainian intellectuals. It published articles that shaped national consciousness and united Ukrainians of different ages and social statuses.

According to revolutionary era politicians, Rada was the school of their civic maturity.

Political Awakening and the Central Rada

The spring of 1917 and the revolution marked a moment when Chykalenko admitted he cried with joy for the first time in his life. Ukrainian flags, Cossacks in traditional garb — everything he had dreamed of came to life.

Though he didn’t take an active political role, he was among those who initiated the formation of the Central Rada. Ukrainian leaders gathered in his home to discuss strategies, draft documents, and plan the future state.

His support helped establish institutions that later became the foundation of Ukrainian independence.

Legacy and Remembrance

In his later years, Chykalenko stepped back from active public life but left behind a monumental legacy. He was a patron of Ukrainian media, literature, music, and historical scholarship.

After his daughter’s death, he donated her savings as a prize for the best work on Ukrainian history — a symbolic gesture of his unwavering devotion to the Ukrainian cause.

He died in 1929 in Czechoslovakia, in forced emigration. His name was erased from Soviet textbooks, but neither censorship nor repression could destroy his legacy.

Today, when we have Ukrainian books, language, media, and an independent state — we must remember that all of this carries a part of Chykalenko’s great love for Ukraine.

Now it’s our turn to ask ourselves: do I love Ukraine only to the depth of my soul, or am I ready to love it to the depth of my pocket?

Залишити відповідь