(film review)

“You know, I’ve been thinking. Everything … just comes together. It’s me. I chose this. I chose all this. This rock… this rock has been waiting for me my entire life. It’s entire life, ever since it was a bit of meteorite, a million, billion years ago. In space. It’s been waiting, to come here. Right, right here. I’ve been moving towards it my entire life. The minute I was born, every breath that I’ve taken, every action has been leading me to this crack on the out surface.”

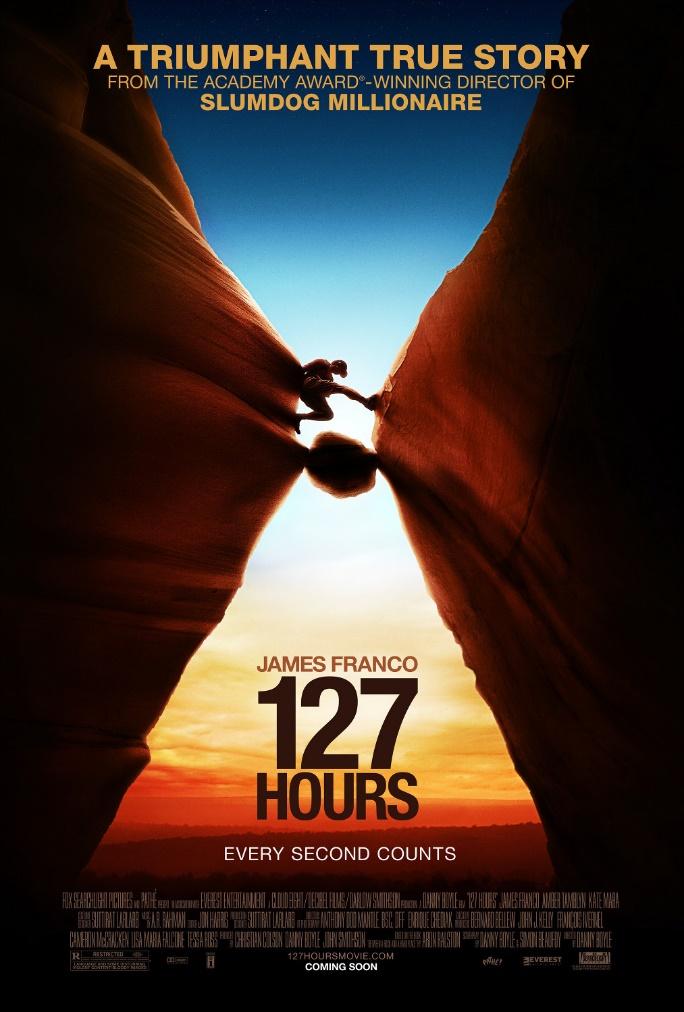

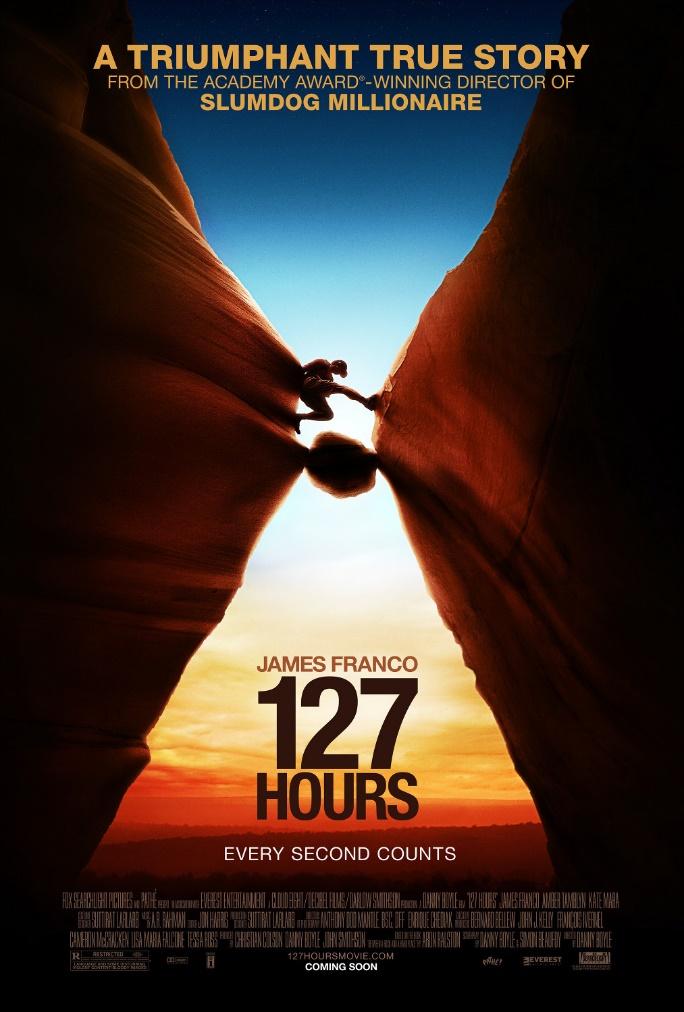

In the summer of 2003, the cheerful loner Aaron (James Franco), this time without warning anyone, went to cycle around the Grand Canyon. There he met two lost girlfriends, swam with them in a pond. With the girls, however, Aaron will only spend a couple of hours, and the next 127 – alone, in a narrow crevice, with his hand tightly crushed by a cobblestone and without any hope of salvation.

Danny Boyle (film director) proves once again that the main character of our time is a young, active sociopath. Having reached the canyon, first of all, quite even smugly Aaron records himself on a video (which, most likely, he will watch later): “Only me, music and night. Super.” The fact that he did not tell anyone about his trip is not a tragic accident, but certainly a movie pattern. At the beginning of the film, a group of cyclists is moving towards him – he casts a quick, uncomprehending glance at them. He is one of those people who instinctively run away from society, erase, without listening, messages on the answering machine, and having stumbled on the track, will certainly take a picture of themselves before picking up speed again. When a hefty stone suddenly falls on this man’s hand, it is not hellish pain that sparkles in his eyes, but the shock of sudden immobility.

“127 Hours”, of course, was conceived as a movie about the triumph of will, and not only of the hero and the actor, but also of the film director himself. There are no questions for the film director. It is as if he doesn’t care that he has to burn fuel without moving away – the main thing is that it is there. Boyle, like his character, reflexively pulls out of his backpack a set of tools tested over the years – sun-drenched panoramas, hallucinations at the limit of visual capabilities, a brilliant soundtrack, the brilliant cameraman Dod Mantle.

The hero is more riveting. Realized the value of life, escaped from the clutches of death – this is all clear. Typical, although, I must say, based on real events, the story of willpower turns into a sentence to an individual, albeit a very strong person, to a lifelong dependence on society. A person dies, first of all, not from hunger or pain, but from a lack of movement, rhythm, and crowd. It is no coincidence that the film begins and ends with plans for a high-speed metropolis. In the opposition between nature and civilization, Boyle is clearly in favor of the latter (in its own way it is symbolic that the hero decides to take extreme measures after the camera’s battery runs out.). Nature is just waiting for the moment to crush you with some part of her body (“This stone has been waiting for me all my life.”). However, Boyle crosses out this simple morality with a spiritually uplifting ending. It’s better not to think about what exactly his film is, because alas all he wants to tell us is when going somewhere, leave a note on the fridge.

In general, my rating is 9/10.

Залишити відповідь